Moses Drury Hoge, one in a long line of family preachers

By Cecil Hoge

I have mentioned on this blog that I come from a long line of preachers and pirates. In “Grandpa Gets Busted”, I discussed the pirate side of my family, citing my grandfather, Edwin Shewan, who repaired ships for the Atlantic fleet and ran liquor during prohibition. In “Sailing Clipper Ships Around the World”, I recounted some of the exploits my great, great, great, great uncle, Andrew Shewan, who was a captain of clipper ships that sailed from Scotland and England to China and India, sometimes carrying cargoes of a dubious nature. Those two Shewan men came from a long line of sea captains who, the further you go back the more likely it was that they were pirates or privateers appropriating cargoes from Spain or some other unfortunate country…no doubt in the good services of an English Queen or King.

I would like to say that my claim to be related to a long line of preachers is equally secure. In this, I offer up my great, great, great, great grandfather, Moses Drury Hoge, shown above. Not only was he preacher, his father, Samuel Hoge, also was a pastor, as was his father’s father, named, not co-incidentally, Moses Hoge. Given this long line of distinguished preachers, I can say that coursing my viens is the blood of both pirates and preachers. This mixed heritage had left me confused at times and perhaps, sometimes led to a few mistakes in the direction of my life.

Here are some facts about the preacher side of my family. Moses Hoge, Moses Drury Hoge’s grandfather and Drury Lacy were both associated with the founding of a church in Richmond, VA. and with the founding of Hampden Sydney College – both having served as Presidents of Hampden Sydney College. Samuel Davies Hoge wed Elizabeth Rice Lacy in 1817. Samuel was a pastor at Bethesda Church located at the Culpeper Court-house. Moses Drury Hoge was born September 17, 1818.

John Blairsville Hoge, another relative, said at the time of his birth, “Take this child and train it for heaven.”

So it could be said that from birth there were high expectations of Moses Drury Hoge.

Moses was a constant reader, well read both in the Bible and the Classics. He went Hampden Sydney College in 1836 at the age of 18. After graduating, Moses became a trustee of that college at an early age. According to another preacher and relative, Peyton Harrison Hoge, Moses Drury Hoge was “a moral man and shrank from whatever was low and defiling.” In college and afterwards, Moses associated with Christians, many of whom were Presbyterian ministers. At college and as soon as he himself climbed the pulpit, Moses gained a widespread reputation as an orator and preacher. His speeches were considered brilliant and powerful.

In the 1850s Moses had the opportunity to go to Europe. In England he met many Presbyterian Ministers and became acquainted with the leaders of the Church in England.

While still in college, he was approached by the Reverend B.M. Smith, a young minister himself, to become a minister. Moses had all the right stuff…coming from a long line of ministers, preachers & pastor’s, being both serious and religious, well versed in the Classics. Strangely, at the time Moses replied that he doubted he would live long enough. It seemed his early health was not the best and for some time he thought he might die of consumption. That did not happen and some time later, after being approached by more preachers, he decided to enter Seminary School.

He was licensed as a minister by West Hanover Presbyterian Church in Lynchburg on October 6th, 1846. This was the same church in which his father and grandfather had been licensed. Thus three generations of the same family were connected by this strange sequence of events in the same church.

Apparently, Moses was a star preacher and orator from the start. Moses Drury Hoge was thought to be a great and powerful orator. In the early part of 1844, he became a minister at the First Presbyterian Church on Franklin Street, near the Exchange Hotel.

Second Presbyterian Church which Moses Drury Hoge founded and later preached to Stonewall Jackson, Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis and many other leaders of the Confederacy.

His church was crowded from the beginning, Sunday after Sunday.

On March 20th, 1844, he married Miss Susan Wood. They made their home at the Exchange Hotel. At this time, his health still was not good. This changed when he went to Europe. In the spring of 1854, he went abroad for five months to London, Liverpool, Edinburgh, Dublin, Brussels, Antwerp, Cologne, Frankfurt, Zürich, Lucerne, Berne, Milan, Genoa, Turin, Verona, Venice, Lyons and Paris. In doing so, he also visited many of the finest lakes and the grandest mountains in the world. Apparently, it was the trips to the mountains and the lakes that improved his health.

In 1855, after returning from Europe, Moses and a Dr. Moore, another fellow pastor, purchased the Watchman, a respected Presbyterian publication. The two partners changed the name to Central Presbyterian. Moses became the editor of that paper and wrote editorials in that paper from 1855 to 1879.

By 1855, he had three children, one of whom, Fanny, died in 1851. In his travels around the country, Moses preached in Brooklyn at the Academy of Arts. It was gathering of ministers from all over the country and was well-received. His first son was born in 1859. It was around this time that debates about secession became prominent in Moses’s life. Moses did not think of the Civil War as having its origin in the debate over Slavery.

Moses, according to his nephew, Peyton Harrison Hoge, in his book “The Life and Letters of Moses Drury Hoge”, agreed with the words of John Randolf Ticker:

“The North fought for the great political idea – the idea of the Union; the South fought for another great political idea – the idea of local self-government. Preserve the two and the war will not have been fought in vain”.

Apparently, Moses did not approve of slavery. On receiving a number of slaves from his wife’s estate, he offered them their liberty. Interestingly, only one accepted and the others remained with Moses and his wife. At another time Moses bought 5 slaves, the relatives of his hired servants and then set them free.

In any case, Moses Drury Hoge still preached to slaveholders. He may have abhorred the institution, but he did not condemn it. Moses was apparently in favor of sending slaves back to Africa.

“I was pained in observing the extensive disaffection to the Union which seemed to prevail in that part of Virginia. It strikes me if you expressed anything too strongly it was when you spoke of the small number in the South who are in favor of secession, if it could be accomplished peacefully.” Moses Hoge wrote in 1851.

In 1859, Moses wrote to his brother, William Hoge, who was also a minister, at the time preaching in New York:

“Tomorrow is our Thanksgiving Day. One thing darkens its joy. Shall as many States ever again celebrate one day united in one Confederacy? I trust and pray He will save us from the wrath and folly of war. But my own hopes have never been so darkened. The people have in a great measure lost their horror of disunion. I still believe an overwhelming majority love the union.”

But as time went on Moses changed his attitude towards the North. In another letter in January of 1861 he says, “I have considered the state of Northern aggression very ominous for many years.”

And then he writes his brother:

“My Dear Brother: The thing we have feared is upon us. The spirit of Cain is rampart, and we seem about to plunge headlong into an unnatural and diabolical war. We may not long have the privilege of even writing to each other…You are right in the impression expressed in your letter to the Central Presbyterian that Virginia has nothing to expect by way of conciliation or concession from the North…The war spirit is fearfully aroused here, and the fierce demon of religious fanaticism breathes out threatening and slaughter. It is not safe even for a minister to counsel peace.”

By the middle of 1861, Moses Drury Hoge’s opinion of the coming conflict changed and he came to the conclusion that the South was right in its quest to secede. In another letter to his sister June 1, 1861, he says:

“With my whole mind and heart I go into the secession movement. I think providence has devolved on us the preservation of constitutional liberty, which has already been trampled under the foot of a military despotism at the North…I consider our contest as one which involves principles more important than those for which our fathers of the Revolution contended.”

After the war began Moses worked at “Camp Lee”. He wanted to become a chaplain to a regiment, but he was persuaded that he was needed at the center of the Confederacy.

Writing his wife on June 24th, 1862 describing the battle lines being set up at “Nine Mile Road” he wrote:

“The town is now all excitement in anticipation of the battle which is expected to come off tomorrow or next day. Jackson and Ewell are said to be in Hanover, ready to strike McClellan’s army in the flank. The conflict will be tremendous, but I have no fears as the result. I think we will utterly rout our enemies, by the blessing of God, and we live in Richmond in long suspense of it, and of the burden of having two vast armies in its vicinity, consuming everything there is to eat…All my concern is for the multitude who must fall, and for the number of the wounded who will crowd our houses and hospitals.”

Two days later the “Seven Days” fighting began, resulting in the withdrawing of McClellan and the present relief of Richmond.

In the early days of the Civil War or the Disunion, as some called it, there is the curious story of Moses overhearing some soldiers talking.

One soldier said, “I wish all the Yankees were in hell.”

Moses said, “Would you not see them sent to heaven?”

“No I would rather see them in hell.” Said the soldier.

“Oh,” said Moses, “I thought you would probably prefer them to be where there is less probability of your meeting them.”

This apparently caused laughter in the soldiers.

At this time, Moses was also made the honorary Chaplain of the Confederate Congress. Moses wrote his brother, William Hoge, about his many duties at the beginning of the war:

“When you saw something of my manner of life in former days, you thought me a busy man, but I am now the most pressed, the most beset and bothered brother you ever had. My 6 sermons a week, and funerals extra, might fill up all my time reasonably well, with pastoral visits thrown in to fill up the chinks, but it is only the beginning of the Illiad. I have opened Congress every day this session…life of late has been all work and no play with me…I have been preaching the last three Sunday afternoons to the Fourteenth Regiment near the reservoir.”

In another letter to his brother, he wrote:

“I had my first sight of the enemy day before yesterday…The enemy’s pickets were about 500 yards distant, in full view…It gave me new indignation to see them walking and riding about in a locality which I was so familiar. McClellan has his headquarters at friends Webb…There is no panic among our people. Resistance is to the death and is the calm determination of the citizens and our soldiers are confident of victory.”

As the war proceeded Moses found himself closer and closer to battles. Here is a description by Moses of The Battle of Seven Pines:

“We halted a moment at a building about two miles from the disease of the battlefield where we saw a great number of our wounded – which had been brought and laid, some of them on the floor, and others on the ground around the house – the surgeons standing over them with bloody hands and knives, busy making amputations, bandaging up wounds…Before reaching this building, we saw many of our men wounded, yet able to walk, staggering towards the city, other were conveyed on horseback, in ambulances, or in litters, carried by their comrades. Some of these men were groaning, others seemed ready to faint with pain or loss of blood, while others went along sang froid.

“Passing the temporary hospital, near the roadside, I begged to go in and take a look at the condition of things there. It was a spectacle at which the Angels might weep! No one knows what war is who has not seen military hospitals; not of the sick but of the cut, maimed and mutilated in all the ways in which the human body can be dishonored and disfigured. Inside the hospital on the floor, the men lay so thick that it was difficult to walk without stepping on them. I kneeled down and prayed for God to comfort them, give them patience under their sufferings, spare their lives, bless those dear to them, and satisfy to them in their present trials.

“On the ride back to town, the scene which the road presented was one never to be forgotten. Artillery and baggage, wagons were coming out, while ambulances, hacks, buggies and persons on horseback were going in. These meeting in narrow places, blocked up the way. Omnibus and other heavy vehicles were stuck fast in the mud, which drivers were trying to prize out; and in the midst of the noise and the confusion the groans of wounded men, jolted and jerked about, could be heard everywhere. I was glad when the first gas lights of the city came in view, fatigued as I was, covered with mud, and wet from wading the swamp road after I gave up my horse to the wounded boy. I immediately went off to the War Office and found Secretary Randolph still in his house. I gave him some account of what I had seen…on reaching home, I found good Susan, standing in the front door, watching and waiting for me.”

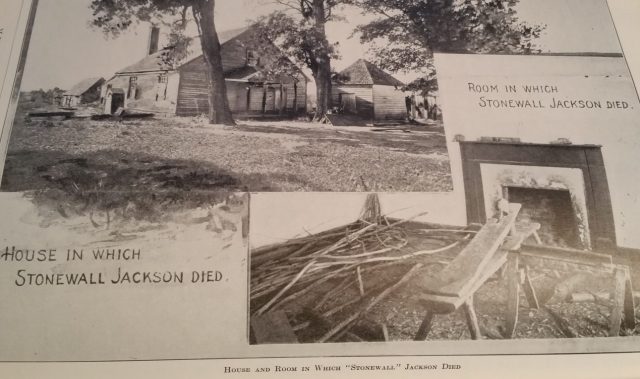

In the first years of the Disunion, Stonewall Jackson came to Moses Hoge’s church and listened to many of Moses’s sermons.

The beloved Stonewall Jackson

As a sign of his respect and trust, Stonewall Jackson gave Moses the following pass:

Headquarters, Valley District, Near Richmond

“Permit the bearer, the Rev. Moses D. Hoge, to pass at pleasure from Richmond to any part of my command.”

T. J. Jackson, Major General

General Jackson was a member of Moses Hoge’s congregation and General Lee was a close and personal friend. Moses’s friendship and association with Stonewall Jackson grew until Jackson was killed.

In 1863 Reverend Moses Hoge took a steamer from Charleston to England in order to get 35,000 bibles, prayer books and testaments. This was a dangerous mission because they had to run a blockade and the captain had instructions to scuttle the ship if capture was imminent. That meant that the passengers would have to get on small boats at the last minute, and make their way to shore. Moses wrote to his brother explaining this and asking him not to tell his wife who would be terrified.

Later, in a letter to his sister, after he had successfully passed through the blockade, Moses wrote enthusiastically about this escapade:

“Our run of the blockade was glorious. I was in one of the severest and bloodiest battles fought near Richmond, but it was not more exciting than that midnight adventure, when, amid lowering clouds and dashes of rain, and just wind enough to get up sufficient commotion in the sea to drown the noise of our paddle wheels, we darted along, with lights all extinguished, and not even a cigar burning on the deck, until we were safely out, and free from the the Federal fleet. In Nassau we chartered a little twenty-ton schooner, hired a crew of negroes, and made a fine run to Havana, where we got on the Royal Mail Steamship Line, to St. Thomas, and so to Southampton.”

In London, Moses gave an account of the Southern cause to Lord Shaftsbury who then announced that they would send 10,000 bibles, 50,000 testaments and 250,000 portions of the Psalms and Gospels.

Among the many people that Moses met when he was in England, was Thomas Carlyle. Apparently, Carlyle, because he was interested in the right of the Able-man to rule, took a steep interest in the Confederate cause. While Moses was obtaining bibles in England, his brother William was visiting Stonewall Jackson’s troops near Fredericksburg to engage in mission work among the soldiers. Shortly thereafter, Stonewall Jackson was killed in an unfortunate accident, shot by his own troops.

William Hoge, Moses Hoge’s brother, wrote his wife about Jackson’s funeral. Here is part of his letter:

“So I will begin with “Gordonsville”. About ten minutes after I our train arrived, the special train came slowly around the curve, bearing it’s sad, precious burden, the dead body of our beloved glorious Jackson. As it drew near, the minute guns, the soldiers funeral bell, sounded heavily. How strange it seemed that a crowd so eager should be so still, and that Jackson should be received with silent tears instead of loud-ringing huzzas. As the train stopped, I caught sight of the coffin, wrapped in the flag he had borne so high and made so radiant with glory so pure. Many wreaths of exquisite flowers, too, covered it from head to foot. Sitting near the body were young Morrison, his brother-in-law, our dear friend Jimmy Smith, and Major Pendleton.

“I asked if Mrs. Jackson would like to see me. And there sat this noble little woman in her widow’s weeds, a spectacle to touch and instruct any heart…And there, just before her lay her sweet little babe, little Julia, named by him for his mother, the babe he had never seen till her recent ten days visit abruptly ended by the great battle; the babe he delighted in…here it lay on its back, the best little thing, looking so tender and so unconscious of its part in these tremendous scenes, not starting, or ceasing the meaningless pretty motions of its little hands, as the cannon thundered.”

While Moses was in England, he also learned of the death of his son, Lacy Hoge. Soon afterwards, Moses returned to the States, first sailing to Halifax and then going to Bermuda. From there Moses steamed in the blockade-runner, “The Advance”. As they came to Wilmington and Cape Fear the Northern fleet was in full view. The captain, apparently drunk at the time, steamed ahead and soon they were fired upon by the Northern fleet. Fortunately, they came within range of Confederate guns at Fort Fisher and soon they were firing at the three Northern ships pursuing them. While this situation was not helped by the captain being drunk as he approached Wilmington, it perhaps gave the captain the courage he needed to run past the three Northern ships.

For Moses, now safely landed, the contrast between London and Wilmington apparently was stark. Wilmington had been decimated by yellow fever earlier that year and was a terrible and forlorn comparison to the bustling and prosperous London. Perhaps, more discouraging was the fact the his bibles and testaments never did make it to the Confederacy. They were captured December 6th, 1863. So it could be said that his mission was a failure.

Moses was able to carry some sample bibles with him which he then sent to various Confederate military men. And Moses did receive several letters of thank you from leading generals in the Confederate army, including letters from Robert E. Lee and Jeb Stuart.

In 1864, his brother, William Hoge, died, adding more sorrow to Moses. Apparently, after preaching and working in hospitals, William Hoge’s strength gave out and he passed away.

As the end of the Civil War approached, it fell to Moses Hoge to write a resolution appointing a day of fasting and prayer. Moses also accompanied Jefferson Davis and his cabinet as they withdrew from Richmond. If he had remained in Richmond he would have to take an oath of allegiance to the United States. Moses was not willing to do that as long as the Confederate Government existed.

After the war, Virginia and all the Southern States were governed as a conquered province by military law and martial authority. It must have been a time of profound despair for Moses. He wrote to his sister in May, 1865:

“I forget my humiliation for a while in sleep, but the memory of every bereavement comes back heavily, like a sullen sea surge, on awaking, flooding and submerging my soul with anguish. The idolized expectation of a separate nationality, of a social life and literature and civilization of our own, together with a gospel guarded against the contamination of New England infidelity, all this has perished, and I feel like a shipwrecked mariner thrown up like a seaweed on a desert shore. I hope my grief is manly. I have no disposition to indulge in lousy complaints. God’s dark providence has enraptured me like a pall. I cannot comprehend, but I will not charge Him foolishly; I cannot explain, but I will not murmur. To me our overthrow is the worst thing that could have happened to the South – the worst thing that could have happened for the North, and for the cause of constitutional freedom and of religion on the continent. But the Lord has prepared his throne in the heavens and His Kingdom rules over all. I have not been very well since the surrender. Other seas will give up their dead, but my hopes went down in to one from which there is no resurrection.”

Moses became very active in helping with the reconstruction after the war, but in 1868 a new personal problem arose. An attack of facial paralysis made speech impossible. This of course meant that he could no longer preach. Fortunately, this condition only lasted for a few months. Thereafter, his ability to preach was completely restored.

During the 24 years of their married life, Moses Hoge’s wife had lost her father, mother, brother, five grown sisters, and four children; the last, little Genevieve, dying at Mr. James Seddon’s, just as their hearts were crushed with the downfall of the Confederacy.

In the spring of 1868, she contracted a fatal disease. On November 23rd, 1868 she died.

General Robert E. Lee

Robert E. Lee wrote Moses a letter condolence to Moses. Here is part of what he said:

“I hope you felt assured that in this heavy calamity you and your children had the heart-felt sympathy of myself and Mrs. Lee, and that you were daily remembered in our poor prayers.

With our best wishes and sincere affection, I am

Very truly yours, R.E. Lee”

Two other disasters occurred in 1868, the Senate Chamber in Richmond collapsed and killed 65 persons and injured 200 others and the President of the former Confederacy, Jefferson Davis, passed away.

Because Richmond was almost completely destroyed, Moses was urged by many to restart his church in some other place. Moses thought this over, but decided to remain in Richmond. This proved to be a good solution in the end and the church in Richmond prospered as Richmond was rebuilt.

In 1872 Moses went north to Princeton College and preached in their chapel. This sermon was well accepted. This led to other sermons in Philadelphia and New York. These sermons were also well accepted. By this time, Moses Drury Hoge was a famous and revered Presbyterian minister.

Moses Hoge also spoke at the World’s Evangelical Alliance. He was invited to speak on the “Mission Field of the South”. His address was well accepted and apparently established his fame throughout the Christian World.

Here is what Moses wrote his sister in October 16, 1873 about his sermon in New York:

“I found the church packed, aisles and all. I preached a sermon I had arranged that afternoon (having changed my theme after dinner) without any notes, and I had what the old divines used to call “liberty” of feeling, thought and expression, which greatly helped me in the delivery.”

Where Stonewall Jackson spent his last minutes alive

In 1875, Moses gave the oration commemorating the Foley statue of Stonewall Jackson. This statue was presented to Richmond by an Englishman sympathetic to the Southern cause. Here is part of what Moses said:

“And now, standing before this statue, I speak not for myself, but for the South, when I say it is our interest, our duty and our determination, to maintain the Union, and to make every possible contribution to its prosperity and glory, if all the States which compose it will unite in making such a union as our fathers framed, and enthroning above it, not Caesar, but the Constitution in its solid supremacy.”

Apparently Moses was upset when the London Times wrote an article suggesting that his speech had political motivations. Moses response was this:

“So far from it, I announced it to be the purpose of the Southern people to maintain the government as it was now constituted, though we should profess no love for a Union in which the Southern States are denied privileges accorded to the Northern.

Moreover, I said, “We accept this statue as a pledge of the peaceful relations which we trust will ever exist between Great Britain and the confederated empire formed by the United States of America.”

Moses was also upset at the New York Tribune because he thought they misrepresented the design and spirit of his speech at the unveiling of the Jackson statue.

Moses wrote, “The celebration here had no political significance whatever. It has not had the slightest political effect. It was not intended to excite animosity especially between the North and the South, not to stir up rancor between Great Britain and America.”

However, according to the account of D.H. Hill, perhaps, Moses got somewhat carried away by the event:

“Dr. Hoge made the mighty effort of his life. He was inspired by the grandeur of the occasion, by the vastness of the audience, and above all by the greatness of the subject of his eulogy. He impressed all who heard him that he is the most eloquent orator on this continent…Dr. Hoge, in closing his address, alluded to the prophecy of Jackson, that the time would come when his men would be proud that they belonged to the Stonewall Brigade. Rising to his full height, the orator exclaimed in his clear, ringing tones:

‘Men of the Stonewall Brigade, that time has come. Behold the image of your illustrious commander.'”

D. H. Hill concluded: “The veil was raised, the life-like statue stood revealed, recalling so vividly the loved form of the illustrious soldier that tears rained down ten thousand faces. Men of sternest natures, cast iron men, we’re weeping like children.”

For the rest of his life, Moses went around the country preaching in both the North and South. There was still a great deal of bitterness and tenderness in both the North and South, so what Moses had to say was not always received well. There was still discord between North and South sections of the Presbyterian Church. Various assemblies were held in the North and South which Moses attended.

Here is part of what Moses had to say at one of these meetings:

“Who are the men who cannot bear the test of the light of our purity. Is there no genuine Presbyterians but ours? If the only pure Church is the Presbyterian Church of these Southern States; if the problem of the development of Christianity as symbolized in the Presbyterian faith and form of government had been solved only by us; if after all the great sacrifices of confessor and maters of past ages, we alone constituents the true Church; if this only is the result of the stupendous sacrifices, on Calvary, and the struggles of apostles and missionaries and reformers in all generations; then may God have mercy on the world and on the Church.”

By the late 1870s Moses was coming to grips with the end of the Disunion and making a new life for himself. In 1877 Moses wrote his sister from New Orleans:

“This is the land of summer most of the year, and of almost perpetual flowers, but the brightest and the most fragrant was the one wafted by a Northern breeze from New Brunswick.

We are having a pleasant time socially. A few of the old families here still retain their wealth and former homes and style of living. I dined yesterday with one of them. As we went in to dinner, the old lady on my arm, in passing the broad staircase there came floating down two young granddaughters all in white, looking like the angels who came down Jacob’s ladder, to bless the men who waited for their coming below.

The dinners have many courses here – with proper sequence, with the proper vegetables served with each meat or bird, and a great variety of wines. Well, it is pleasant to sit by a good old lady at such a dinner (provided her tender granddaughter is on the other side) and take course after course, leisurely, with much conversation between, anticipating the crowning cup of cafe noir and cigar.”

One senses that Moses Hoge and the world in the South are returning to some kind of normalcy and Moses in beginning to enjoy life again.

Moses attended a delegation of Presbyterian ministers, representing the Southern branch of ministers.

Here is what a paper called the Daily Review said:

“Exceptional interest was excited by the appearance of the next speaker, Dr. Hoge, of Richmond, Va. He stepped upon the platform – a tall, spare, muscular man, of military type of physique, and features bronzed by the sun. His manner at starting was almost painfully deliberate, and with cool self-restraint with which he surveyed his audience and measured his ground before he opened his lips deepened the interest which attended the beginning of his speech…he set forth, with great dignity…the leading points of his many sided subject – the simplicity and scriptural character of Presbyterianism, it expansiveness and adaption, and its friendly aspect to other churches.”

In the summer of 1877, Moses went to England to preach and minister there, meeting again with many members of the Church of England. The next summer, he also went abroad. After returning, Moses wrote:

“The old world was not so interesting to me the last time I saw it. I have become somewhat wearied with galleries, museums, and antiquities in architecture, and I find Europeans inferior to our own people in so many respects that I am more than ever contented with my own country.

All we need is the continuance of a free and stable government to make this the happiest country on the globe…I find, however, many thoughtful men look forward to a near future of strife and disintegration, which Heaven may avert.”

In 1880, he went to Italy and then on to Egypt, Palestine and Syria. For the rest of his life, he traveled and remained active as a minister. He died in a streetcar accident at the age of 80 on January 6th, 1899. Apparently, an electrified trolley car ran into Moses when he was driving his buggy. This resulted in his buggy being overturned. While he did not die immediately from the injuries he sustained, it was said that Moses was never the same vigorous man he had been for most of his 79 years of life. He died a month or so later, apparently from complications from the injuries he sustained in his streetcar accident.

In reading about Moses Drury Hoge, I found one thing very strange. If you read his letters you find that Moses was a very passionate man with extremely strong convictions. It had been my assumption that if I read the sermons of Moses Drury Hoge, I would find the same traits and ardent feeling expressed. So, while preparing to write this article, I bought a book entitled “The Perfection of Beauty and Other Sermons” by Moses Drury Hoge.

Now, having been brought as a Catholic, I was familiar with sermons and with the common fact that generally a priest or minister did not have much to say about the present day. Rather sermons always seemed rooted in what happened 1800 to 2000 years ago and have very little reference to any modern day events. Nevertheless, even the most parochial priest would make some reference to some modern day events or ills, be it drug addition, crime in the streets, some far off war or political events affecting our daily lives.

However, in reading the sermons of Moses Drury Hoge, there seems to be little or no reference to what must have been the most important events in his lifetime. I speak specifically of the War between the North and the South, the Civil War or The Disunion, as it had been alternatively referred to.

Moses does make some reference to modern times in “The Perfection of Beauty” sermon:

“Why is it that in none of the great resorts and haunts of pleasure and fashion collections are ever solicited for the suffering poor, for associations organized to advance all the forms of benevolence?”

Moses answers his own question by saying:

“There is but one gate through which the benefactions of the truly charitable forever flow, and that is the beautiful temple. Yes, this is one of the elements that constitutes the beauty of the church, it’s boundless benevolence, it’s wide-reaching, far-reaching, all-comprehending charity.”

Obviously, this was before Welfare, Medicaid, Medicare and Obamacare. Moses goes on to cite the comments of the Poet James Russell Lowell, who when attending a dinner party in London and heard some eloquent guest disparage Christianity. Moses quoted the following comments of James Russell Lowell:

“It is very easy gentlemen, sitting in an elegant apartment, around a table covered with flowers…to speculate about religion in a jocose way…our friends…would do well to be thankful they live in a land where the gospel has tamed the ferocity and beastliness of those who but for Christianity might have long eaten their carcasses…or cut off their heads and tanned their skins like the monsters of the French Revolution…”

Here I wish to interject that there are two sides to every argument. While it is long true that many arguments have correctly been made that Christianity has been a civilizing influence on human beings, human institutions and civilization, there have also been many arguments made that Christianity and the adherence to Specific sects of Christianity has also been the cause of many wars and the deaths of many people.

Moses Drury Hoge’s argument in this sermon, “The Perfection of Beauty” is that Christianity, and specifically Presbyterian Christianity is profoundly beautiful, beneficial and benevolent. Moses ends this sermon with the following words:

“Yes, my hearers, where this gospel goes, Liberty goes, just laws go, education goes, churches are built, all benign and institutions which bless and benefit society appear.”

That seems to as direct as Moses Drury Hoge gets in the printed sermons that I read to referring to his times. His sermons are all eloquent, but they are undated (at least in the book I have) and mysteriously, there it no reference to the war which tore our Union apart and so demoralized Moses. What is the explanation of that? I can only guess.

I have used two main references to gather information on my relative preacher/minister. One is the previously mentioned “The Life and Letters: Moses Drury Hoge” by Peyton Harrison Hoge published 1899. That book contains an amazing of amount of letters that Moses Drury Hoge wrote to his wife, his sister and his brother. It also includes a large number of letters written to him, some by quite famous people of that time. I have liberally quoted from those letters. The other reference is the book I just cited – “The Perfection of Beauty and Other Sermons” published in 1904 by what is ominously referred to as “The Presbyterian Committee of Publication”.

While Moses’s letters refer to Civil War and speak of that time as tumultuous, sad and tragic, the sermons that I have read do not make any reference to those times. In Peyton Harrison Hoge’s book there is mention that many of Moses Drury Hoge’s notes and written sermons were lost in clamor and confusion of the war. I suspect a darker secret.

I can only guess that even in 1899, when Peyton’s book was first published, there was still a great deal of sensitivity to the events and to the long term effects of the Civil War. I suspect the written sermons might actually have been destroyed or that references to the Civil War were actually taken out from whatever sermons did exist. This is, of course, just a wild guess. And I have not fact to cite to say that I am right.

The former President Jefferson Davis

I would like to know what Moses said on the pulpit in his sermons during the Civil War when he addressed Robert E. Lee, Jefferson Davis, Stonewall Jackson and other leaders of the Confederacy. In Peyton Harrison Hoge’s book, which I have quoted extensively, it is said that Moses Drury Hoge preached to over 100,000 Confederate soldiers. My question is what did he say to them? Did he make no reference to the great struggle they were in?

My guess is that he did refer to the great events that they were passing through and that Moses Drury Hoge had much to say about the position of the South.

Did he, for example, get up before his congregation and say with utmost conviction in his loud, sonorous, slow Southern drawl (I am also guessing what his voice sounded like):

“God has ordained that there will be a 1,000 years of slavery and God is on our side. The South will rise to be a great nation and we will live free under the benefice of God.”

Or did he say in a slow, dignified, powerful Southern drawl:

“The Southern States are right and moral in their pursuit of an individual country and an individual civilization, preserving the most honored institutions and examples of our Southern Confederacy. We shall emerge a free country to construct our own civilization as God has mandated we will.”

My guess is that he did not stand up for slavery itself because Moses was reputed to have sold slaves in order to free them. So I would think that Moses was very uncomfortable with the institution of slavery itself. However, I suspect that he did believe fervently, ardently, with all his heart and soul, in the right of the South to revolt and establish their own independent country.

We know that people’s beliefs evolve with time and no doubt the beliefs of Moses Drury Hoge went through several evolutions. Perhaps, as a young man, he believed in the Union as it existed at the time. Perhaps, as the years passed, he frowned on, disagreed with and was against slavery as an institution. But as the Civil War came closer and the movement for secession gained traction, perhaps, Moses came to be a fervent and ardent supporter of the Disunion, a believer in the rights of individual States to decide their own future and their own fate.

After the Civil War, Moses views and ardent opinions probably changed again with the new times and the new reality that the South had lost.

On July 2, 1881, President Garfield was assassinated. This sent, in the words of Peyton Harrison Hoge, “a thrill of horror through the country”.

By a strange co-incidence, Moses happened to be near New York City at the time of Garfield’s death. The funeral for President Garfield was to be held at The Fifth Avenue Church in New York. The pastor of that church happened to be traveling and was not able to give the oration for the funeral. After asking many ministers and preachers around who might be a good replacement, The Fifth Avenue Church were recommended Moses Drury Hoge to give the sermon for President Garfield’s funeral. And so they did.

Here is part of Moses’s oration:

“Our present sorrow shows how God, in his provenance, can arrest the attention of the world, and make the heart of humanity tender, and so cause all to feel the dependence of man upon man, of State upon State, and of nation upon nation. The news of the attempt of the assassin was flashed all over the world, and then across all continents, and under all seas came electric messages of sympathy and condolence – China and Japan uniting with the states of Europe; paganism and Mohammedanism joining with all Christendom in the expression of common sorrow. Thus God makes the very wounds of humanity the fountains from which issue the tenderest sympathies and the sweetest charities which bring comfort to the suffering, which at the same time, make the whole world akin in the consciousness of common interests and interdependence.

“More practically important to us is the fact that the great bereavement we commemorate today has hushed the voice of party clamor, and at once rebuked and silenced the discord of sectional animosity.

“Death is the great reconciler.

“A Federal officer was mortally wounded on one of the battle fields of Virginia. As he lay upon the ground, far from his comrades, conscious that his end was near, while scattered soldiers of the Confederate Army went swiftly by, he called to an infantryman who was passing the spot, and asked him if he would offer him a prayer. The man replied “My friend, I am sorry I cannot comply with your request. I have never learned to pray for myself;” but he did what he could; he moved the officer into the shade, put something under his head, gave him some water out of his canteen and then hurried on. Presently a dismounted Union cavalryman, who had lost his horse came by. The confederate officer called to him and made the same request, “Won’t you stop and say a prayer for me?” The trooper kneeled down at the side of the dying man and commenced a prayer but as he uttered one tender petition after another, the officer used the little strength that remained to him in creeping closer and closer, until he placed both arms around the neck of the petitioner, and when the last words of the prayer were uttered, he was lying dead on the bosom of his late antagonist in battle, but in the parting hour he was one with him in the bonds of the gospel, a brother in Jesus Christ – united in love forever.

“Yes, death is the great reconciler.

“I am here today, while making a brief visit to a friend in an adjoining State, taking the only rest I have had for a year, an invitation came from the officers of this church urging me to perform this sad office in the absence of its honored pastor; and I stand here to represent the feelings of the Southern people, whose interests and whose sentiments are mine, and to say that today your sorrow is their sorrow, and your bereavement theirs. Today Richmond and Augusta and Charleston and Savannah and Mobile and New Orleans, unite with Boston, New York, Philadelphia, Cincinnati and Chicago, in laying their immortelles on the tomb of the dead President. Today there is a “solid South” not in the low and unfriendly sense in which demagogues use the phrase, but in the nobler sense of a South consolidated by a common sorrow; and one with you in the determination to advance the prosperity, the happiness and the glory of the Union, and that, too, without the surrender of one just political principle honestly held by them. This is the day for the inauguration of a new era of harmony and true unity. The great calamity will thus be overruled to the good of the whole land.

“The providence of God sometimes wears a frowning aspect as it approaches, and men’s hearts grow faint with foreboding; but as the providence, which looked like a demon of darkness drew near, is passing away, it turns and looks back upon us with a face sweet and bright as the face of an angel of God. So now the angel of death seems to menace the land over which he is casting his dark shadow, but lo! As we look we see him transfigured. It is the angel of love, dropping peace and goodwill upon the world.”

We can tell from this oration that Moses Drury Hoge’s adamant and fiery feelings from the Civil War had mellowed and there came a kind of peace to Moses.

Moses Drury Hoge’s trek through this world, while already long, was not yet done. In 1884 he went abroad with his oldest son, who had been pursuing his professional studies for two years in Berlin. He also visited England and went to Copenhagen. He gave sermons and orations in almost every foreign city he visited.

As further time passed, Moses became more and more at home with the change and evolution of his country after the Civil War. One could say he was almost becoming cheery.

In 1888, he again went abroad and attended the London Council of the Presbyterian Alliance. On July 11th of the same year, Moses wrote about a lucky circumstance that occurred while in London:

“It is like telling one’s dream, but it is a waking reality that I am the sole occupant of one the most elegant houses in the West End of London, on one of the most beautiful squares. It happened in this way. For ten days I was at the De Kayser Royal Hotel hard by Blackfriers Bridge; but while I was taking “mine ease in mine own inn,” one of London’s pastors told me a wealthy lady, a member of the church had gone to Scotland to be absent all summer, but had expressed the earnest wish that her’ house be occupied by members of the Alliance during its sessions, and he invited me and another delegate from the South to accept the proffered hospitality of his parishioner… my fellow member had to decline, but, I accepted it and…I found the kind pastor there to receive me and put me in the good care of the good housekeeper.”

So Moses Drury Hoge’s later life had its pleasant surprises.

A grainy picture of Moses Drury Hoge in later life

He continued throughout his life to preach all over the world and all over this country. At times he said things that were committed no time and true for all time. Here something that sounds more as if it came from Confucius, not a Southern Presbyterian minister:

“A nation is but congeries of families, and what the family is, the nation will be.”

He spent 3 summers preaching in Baltimore in the steaming heat of that city. And his letters about that time, not only shows how truly busy he was in old age, but also that he possessed an active sense of humor:

“I was never more thoroughly well than I am this autumn,” he wrote, “although I worked steadily through the entire summer without a day’s rest. It was the hottest summer, too, known for many years.

“I had to go to Bridgeton, NJ on the 20th of July to deliver a centennial oration. It was a day of the most intense heat, so statisticians assure us, for twenty-one years. I spoke in a Grove to two or three thousand people in the afternoon the mercury marking one hundred and one degrees, and made my oration at night in the the church, but I do not know what record the thermometer made of the temperature. It exceeded anything I ever experienced, and when I returned to my room at the hotel, I sat most of the night in the window, sucking lemons and drinking ice-water. I passed the ordeal, however, so well that I converted to the theory of evolution from the lower animals, and think that one of my great ancestors was a salamander.”

As evidenced by the quotes above, Moses was busy and active all his life and, as time passed, his beliefs further moderated and changed. Perhaps, he came to think of the Civil War as the will of God. Perhaps, he came to think of the great and bloody Southern effort to secede from the Union as meant to fail. Perhaps, he came to think of this Great War as the glue which would forever make the American Union strong and immutable to further change. Of course, we all know nothing is immutable to change.

When I got the idea to write something about my great, great, great, great grandfather, Moses Drury Hoge, what intrigued me was here was a man of God, on the side of the South, who preached to Jefferson Davis, to Robert E. Lee, to Stonewall Jackson, to tens of thousands of Confederate troops, to the Southern people. I thought in the beginning it must have been a difficult moral position to be in…to be preaching for freedom in a land based upon slavery.

At the time, I had no real idea of who my relative really was. As I started to do research and discovered that there was an enormous amount of written information about him, I began to be amazed, surprised and then impressed, not only by what words were written about him, but also by his own words, which were so extensively quoted and which I have so liberally re-quoted.

As I read more and more of what Moses said and did, I came to understand that he was much more than the man I thought he was. One thing was fairly clear early on, as read more and more of his letters: Moses was an incredibly eloquent writer and I presume, an incredibly powerful orator. Obvious testament to this was the very breath and scope of his vocabulary. Yes, it was Biblically based, but it also was Classically based. I can only think he must have been far better read man than myself or most people today.

When I came to the time of the Civil War and Moses Drury Hoge’s descriptions of that event, I came to see it for a what was. A searing event that forever changed America and changed Moses. His descriptions of the battlefield, of going through a Confederate hospital, of walking home from the battlefield were detailed, harrowing and rang with sad and horrifying truth. I know many true and forceful things have been written about the Civil War and that there is an enormous amount of material on that conflict. But somehow, when I read the words of Moses Drury Hoge, that war became more near, more terrifying and more sad in my mind.

I think Moses was a truly great man. At the same time, I think he must have been a man conflicted on the inside, surely and clearly knowing that when he preached individual states freedom for the South, it could not continue as long as the South was the home of slavery. So at bottom, inside, Moses was conflicted. This does not show up in his outward words, but it must have been true in his inner self.

I would like to quote the end of Moses Drury Hoge’s oration on Stonewall Jackson:

“In the story of empires of the earth some crisis often occurs which develops the genius of the era, and impresses an imperishable stamp on the character of the people. Such a crisis was the Revolution of 1776, when thirteen thin-settled and widely-separated colonies dared offer the gage of battle to the greatest military and naval power on the globe…

“After innumerable reverses, and incredible sufferings and sacrifices, our father came forth from the ordeal victorious…

“But this day we inaugurate a new era…We come to honor the memory of one who was the impersonation of the Confederate cause…And at last it is Jackson’s clear, ringing tone to which we listen:

‘What is life without honor. Degradation is worse than death. We must think of the living of who are to come after us, and see that by God’s blessing we transmit to them the freedom we have enjoyed.’

“Heaven hear the prayer of our dead, immortal hero.”

So, Moses concluded his oration to Stonewall Jackson in 1875.

I cannot guess what the truth is about Moses, I cannot know how he really felt inside and I do not know how his beliefs finally evolved, but I would love to know and I think whatever he came to believe might have some lesson for us today.