Olga in her younger days

By Cecil Hoge

That is not exactly true. Olga never heard of the word “blog”, but she did ask me to write about my family. Olga, whose full name was Princess Olga Ivanovna Obolensky had read some of my articles in Dan’s Papers. This was sometime in the early 70’s. Apparently, my articles were enough to convince her that I should write about my family. Here is what Olga actually said.

“You should write about your family like Masha’s great-grandfather.”

Masha was Masha Tolstoy and Masha’s great-grandfather was Leo Tolstoy. I had met Masha at a Russian Blini, which is a kind of pre-lent festival celebrated with a kind of Russian pancakes and a whole lot of vodka. I remember heading out one evening with Masha and some of her friends to some Greek place in the city to dance and drink Ouzo like Zorba the Greek. Masha was a wonderful, fun-loving girl, but writing like her great-grandfather, well, that was a stretch.

I should probably tell you how I came to how I came to know Olga, have Russian relatives and, in the process, meet Masha Tolstoy. My aunt, Barbara Hoge, married Ivan Obolensky, who was also a Russian Prince, if you can be a Russian Prince after The Russian Revolution. Ivan was the son of Olga. When Ivan and Barbara came to be married, I came to meet and be related to Russian princes, princesses, dukes and duchesses.

One of the houses the Obolenskys lost

In the 1950s and 1960s New York City was a kind of center of displaced Russian aristocrats. Since the Russian revolution, they had lost the houses, the factories and the villages they had owned, not to mention control of their government. First, the Russian aristocrats (those that survived and left Russia) migrated to England and Europe, but by the 50’s and 60’s, many had moved on to America.

So when my aunt married my new uncle, a whole bunch of Russians came into my life.

This was because my father’s family was quite close and anyone coming into the family met everyone else in the family. So for Christmas, for Thanksgiving and for summers out in the Hamptons, all my family would gather together, Russians included. And this led, inevitably, to meeting Olga and Vladdy and Masha and Ivan and Alex and Dimitri and many other Russians, some of whom were relatives and some of whom were just friends.

About 50 years later, I decided that Olga was right. I should write about my family. I feel she would approve of this blog, even if it is not “War and Peace”.

This brings me to Olga’s story which, by turns, is interesting, tragic and extraordinary. Olga grew up in the court of the Czar. She was in her twenties when World War I and the Russian Revolution began. What that time felt like, what it was like to live in Russia as a princess, what it felt like to live in Russia as a common person or as a serf, what Russia itself was like in days of Rasputin, in the days of Czar Nicholas and his wife, Alexandra, in the days before the Revolution, all that is lost to time and hard to imagine. We can read about it, but understanding and feeling it is a different matter.

Here is her story, as much as I know of it. Olga was born in 1891 and married young, at age 19. The man she was married was Petrik Obolensky, her second cousin. In the years before the Revolution they were happy and had 2 sons, Ivan and Alex.

Olga with Ivan before he walked out of Russia

The times were full of change. World War I and soon the Russian Revolution was upon her.

After she came to the United States in 1948. Olga wrote her memoir. While this book has yet to be published, I will quote a few things from the first three chapters of her book which have been published. Here is what Olga said about the onset of the Russian Revolution and the upper class youth she grew up with:

“In the years preceding the October Revolution, the upper class youth had no interest in politics leaving it to their parents, uncles and aunts – considering politics an occupation of the ‘old folks’.

I remember it well from my childhood. After long dinners, with plentiful, exquisite food, the older generation, whose members for the most part occupied important official government positions, would either retire to the library or remain in the dining-room for coffee and liqueurs. There, ensconced in large, soft armchairs, they would spend hours arguing about current political events with great excitement.

The elders never talked to young people about politics: most probably assuming their lack of interest, they considered it unnecessary. Thus, the high-society youth must have been the social group the least prepared to face the Revolution. When it broke out, my husband and I were puzzled by the events and had no conception whatsoever of its potential repercussions.”

But Olga did have some understanding of what was happening:

“At the end of October 1917, the situation in the country became highly threatening. We had the feeling that we were sitting atop a volcano.”

As the days went by the Russian Revolution first took a moderate turn and became the Kerensky Government and then took a more violent turn and became the Bolshevik Revolution. At that point things got a lot worse, at least for the aristocracy. Czar Nicholas and his wife, Alexandra and their children were imprisoned and then killed by the Bolsheviks. Other aristocrats were gathered up and either killed or put in jail.

Here is another excerpt from the opening chapters of Olga’s book:

“Suddenly I was seized with an instinctive feeling of fear. The huge crowd which had by now surrounded our house was easily capable of smashing everything in its path–the iron shutters, the doors, the windows–and then breaking into the house. Already the people outside were standing next to our entrance. What would happen next?

Taking no account of what was happening at that moment, I hurried to my bedroom, where I quickly took off my diamond earrings, the rings on my fingers, and all the other valuable jewelry that I usually wore. ‘It will be better that way,’ I thought. Next I put on the simple black coat which I wore when working as a nurse (sister) at the hospital and covered my head with a mohair Orenburg kerchief. Then, slipping my jewels into the pockets, I hurried back to the hall. The crowd outside was still standing silently waiting.”

It did not take long for the police to find Olga and her husband, Petrik. They were thrown in prison by the Cheka, the secret police, in 1920. Because men and women were put in separate prisons, Olga went to a women’s prison and Petrik went to a men’s prison.

Olga’s mother, Alexandra, and two sons, Ivan and Alex, were not arrested and they stayed in St. Petersburg while Olga and her husband were incarcerated in separate prisons.

Olga lived in prison for a total of 8 months. At first, she was placed in a solitary confinement cell in a “death row” section where many of her fellow prisoners were systematically taken out and shot. Everyday she was told that the next day she would be shot. But the next day for her to be shot never did come and she never was killed.

What happened is for the first two months she lived in 3′ wide by 6′ long cell. The conditions are almost impossible to imagine. Three sides of her cell was constructed of rough wooden boards, the 4th side was stone. There was no window, no ventilation, and almost no air to breath. On the ceiling of her cell was a bright electric light that was un-reachable and on 24 hours a day. Her bed, if you can call it the that, was some fabric from sacks and some straw. Food consisted of some stale bread and hot water that came once a day. There were insects of all sizes which would crawl all over her whenever she lay down. The walls and floors of her cell was covered with alive and with squashed insects.

Almost every night she was taken out of her cell and mercilessly interrogated by the Cheka, the secret police who had arrested her. Often, she was not returned to her cell until just before dawn. And each day, she was told she would be shot the next day. For all of this time, Olga had to live in the same clothes she had been arrested in. These became more torn and tattered and sweat-stained as each day passed.

As hard as this is to comprehend, it must have been harder for Olga to comprehend. Remember, she grew in the court of Czar. She was used too elaborate jewelry, beautiful clothes, fine foods. She was brought up on large estates, she was entertained on large elegant yachts. Her life before the Revolution must been one of incomprehensible luxury. So the transition from princess to prisoner, from palaces to prison, must have been even more incomprehensible and more horrible for her.

Olga stayed in solitary confinement in her 3′ by 6′ cell for over 2 months and everyday must have been a living hell. Her only opportunity to get out of that cell and breath some fresh air was when she taken nightly back and forth to the Cheka, to be questioned and shouted at and tortured mentally and physically for hours. Then one day after two months, for reasons she was never to learn, she was sent from her 3′ by 6′ cell to the Women’s General cell. By that time, Olga was exhausted, delirious, temporarily deaf and almost dead from her treatment in solitary confinement.

Olga stayed in the Women’s General Cell for another prison for 6 months. There conditions were better with food and water two times a day. Conditions were still terrible. Each day she was eating stale bread, sickening soups, living with rats and insects in the women’s section of the prison, with no heat and only straw and sackcloth to sleep on. She still had no clothes other than the clothes she came with.

When you think about it, this must have been a strange and horrifying change of life. When she and her husband were arrested, Olga’s life took another terrible turn. Not only was her husband sent to another prison, but she was also separated from her mother and children. Quite simply, nothing would have prepared her for World War I, the Russian Revolution, the fall of Czar and his government, the loss of all their family’s land and property and her time in prison.

As mentioned, Olga did sense that some terrible change was coming when she started hearing the commotion outside of her house and the louds shouts of revolutionaries protesting in the streets, but the situation became grave in too short a time to understand truly what was going on. Apparently, the butler came to their breakfast table with their newspapers and informed Olga that most of the servants had left the house. Olga had only a short time to sew some jewels into her dress and leave. Apparently, this happened to many people of her class. There simply was no time to understand that their way of life had disappeared.

A strange side story which occurred before The Revolution is that some of Olga’s fellow aristocrats organized the murder of Rasputin in 1916. For those of you who do not know who he was, Rasputin was a Russian priest who exercised extraordinary, almost mystical control over Czar Nicholas’s wife because only he (Rasputin) was able to help Nicholas and Alexandra’s son Alexis with the disease he suffered from. This was Hemophilia, a blood disorder that results in bleeding or death if bumped or bruised.

Rasputin might have been a priest, but he was no man of God. A drunkard and a womanizer and a man of strange spiritual powers, Rasputin spent his time corrupting princesses and staying drunk. These episodes were known to the public and this scandal was thought so bad that it would bring down Czar Nicholas’s government. Many of Czar Nicholas’s friends and relatives were urging him to get rid of Rasputin, but the Czar would not because he and his wife believed that Rasputin was the only man in Russia who could heal their son, Alexis, or at least, keep him from dying. And in truth there were several documented instances of Rasputin coming to the side of Alexis when he appeared to be dying from an episode of Hemophilia and there are documented instances of Czar Nicholas’s son recovering at least temporarily from this strange disease. It was said that Rasputin had a strange Godlike power to reverse the bleeding.

It is strange to think that a single man could change and influence history, but it was surely true that Rasputin was one of the causes of the Russian Revolution. To be sure there were many causes of the Russian Revolution – poverty, famine, injustice, a government unable or unwilling to rectify these failings, but the issue of Rasputin and his relationship to the Czar and, in particular, to the Czar’s wife was an enormous problem. It was rumored in the streets that Rasputin had put Alexandra under a spell. It did not help matters that Alexandra was German and did not speak Russian very well.

I cite this story because even if Olga was only in her 20s at the time, she must have known something terrible was going on and something was very wrong as early as 1916.

Just being in prison must have been terrible enough, but to be told every day that the next day you would be executed and to live on stale scraps with insects crawling all over your body and your cell must have been an experience in horror that is untranslatable and impossible for us to understand.

Then one night, in the middle of the night, Olga was released from the Women’s General Cell without explanation. Shortly afterwards, she made her way to Petersburg and was reunited with her mother and her two children where they were able to enjoy a simple Christmas together.

But there were still changes and hardships to come. Almost immediately, the Cheka began again to harass Olga and her family.

It was at this time that she determined to smuggle her two children, Ivan and Alex, aged 7 and 5, with the aid of a former footman. Ivan, and Alex and the footman literally walked through forests overland north through Russia and then through Finland. There, they were finally able to take a boat from Finland to France.

Olga was not to see her two sons for over 20 years.

Olga herself stayed in Russia, moved to the city of Kalinin and changed her name to Olga Zvezdino in an effort to avoid government scrutiny and reprisal. She lived Kalinin for many years through the depression years until the beginning of World War II. In this period, Olga lived a drab, Soviet style life, with no money, working as a nurse in the local hospital. Eventually, Olga became the head nurse in her hospital. Again, the contrast of her early life with her later life in Russia must have been hard for her to bear.

In 1941 Kalinin began to get bombed by the Germans and the city descended into chaos, creating more misery for Olga. In late 1941, the Germans invaded the city of Kalinin and because Olga spoke German, she worked as a health medical inspector for a few months. Olga then decided to leave Kalinin and literally walked with group of German soldiers and Russian refugees to Germany, almost dying in the process. Towards the end of this exhausting walk, she collapsed in the snow and was left behind by the group because they could not carry or wait for the weak. It was a compassionate German soldier who found her in the snow and actually carried her to the German border.

Telling this story almost makes Olga’s life up to this point seem surreal, but her subsequent life was also full of many changes.

Olga finally got to Berlin in 1943 where she began her life yet again. Here she was to find a distant relative who able to help restart her life again. This relative helped locate her son Alex and got her permission to go to France and meet up with him in 1943, after 22 years of not seeing him. At that time she still did not connect with her son Ivan and her mother Alexandra.

When Olga returned to Berlin, the situation there started to go downhill. The bombing of Berlin became daily and Olga had to hide out in churches and hardened buildings to avoid being killed. Day after day, the bombing escalated and the situation became more and more desperate. In spite that, Olga lived through and survived the bombing of Berlin in 1944 and 1945.

In an incredible coincidence, Olga happened to be living just a few blocks away from my future step-mother. This meant that two of my future relatives lived in and through the bombing of Berlin in 1944 and 1945. So, my future stepmother and my future great aunt lived in Berlin all through the carpet bombing and fire bombing of that city.

Just before the end of the war, Olga moved to Hamburg and finally reunited with her son Ivan after 24 years. After the war, Olga and Ivan went to France and there she was reunited again with other son, Alex, in Paris. Unfortunately, by this time, Olga’s mother had died. In Paris, once again, Olga began yet another new life, this time with her two sons and other Russian refugees.

Olga lived in France and then went to Hamburg, Germany with her two sons up until 1948. What the post World War II period was like in Hamburg for her and two her sons and the many refugee Russian aristocrats huddled in different parts of Europe is hard to know. So much had changed. I think you could say they found a new life and Olga found it better than living in a prison or living in the Soviet Union after the Russian Revolution. I am sure that even though some sort of normalcy had been restored, life was still difficult and anything but secure.

In 1948 Olga and her sons came to New York on an over-crowded boat in rough seas. The journey took 11 days. The post World War II world was rebuilding itself and Olga and her sons came here to seek new opportunities and find a new life.

How my uncle to be came to meet my father’s sister is still something of a mystery for me. I do know my aunt Barbara was active in organizing many charity balls and life and society was also reorganizing itself here after the earth-shaking events of 2 world wars, The Russian Revolution and the terrible depression of the 1930s.

As I understand it, Olga, Ivan and Alec found a new life in New York, meeting with other Russian aristocrats. Ivan, at the time, began living in Southampton with Angier Biddle Duke in what was known as the Duke Box – this was a group of very eligible bachelors living in Angier Biddle Duke’s house. What I know for sure is that Barbara and Ivan met and came to be married and Ivan ended up being the sole representative in America of Taittinger Champagne for Kobrand Industries.

Kobrand Industries distributed Beefeater Gin, Taittinger Champagne and a lot of other alcoholic beverages. The company itself was owned by Claude Taittinger. It turned out Claude thought his brands would be better sold if a Russian Prince represented his line. And that is what happened. Olga ended up living in an an apartment on 98th street between Madison and Fifth Avenue. This was quite convenient because my grandmother had an apartment on 97th street between Madison and Fifth and my uncle Hamilton Hoge lived with his wife and children at 1150 Fifth which was on the corner of 96th Street, just across from Central Park. Adding to the convenience of it all was the fact Barbara and Ivan moved into an apartment on 94th and Madison. So, I ended up having about 20 relatives in a 6 block area. My father and myself (when I was in town) lived in various apartments from 60s to the 70s to 104th street.

This all meant that we all got together as a family quite often. That was the beginning of meeting and greeting many Russian aristocrats who would come by Barbara’s apartment and drink and smoke and tell stories of the 2 wars, of the Russian Revolution and of times in between and of the time before when they lived in palaces and estates and on yachts and had more money than God and were served on hand and foot.

Of course, many things had changed. Most of these Russian aristocrats were now poor. A few were fabulously successful. Serge Obolensky was one of the successful ones. He came to visit often on holidays. He seemed to have led a charmed life, having left before the Russian Revolution started and having gone to England to live among other aristocrats. Serge had an exotic and exciting career as a Colonel during World War II – he was reputed to be the oldest man to parachute into France. He went on to marry Alice Astor after the war, come to the States, dance with Jacqueline Kennedy and be a man about town just about everywhere you could be a man about town.

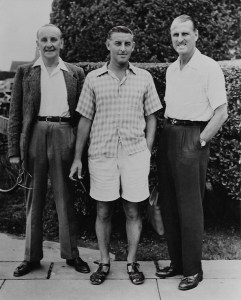

Vladdy, Ivan and Serge entering the Southampton Bathing Corporation

Serge would come over to the 94th and Madison apartment where he would come by and have one or two drinks and sometimes dinner. When he came in, he would give my aunt Barbara a hug and say, “Hello, Dahling.” After an hour or so and a pre-requisite martini, he would look up and say, “Dahling, I must be going.”

And out he would go. That is my memory of him.

We did see a lot of other relatives and other refugee aristocrats – the building on 94th street was full of Russian and French refugees and they were fun crew to be sure. They took a little getting used to, trying to understand what they were talking about. This was not helped by the fact that half the time they were talking in Russian or French or German. But even if you did not understand everything they were saying, you could get the jist of most of what they were talking about. And what came through loud and clear was that they were a very exotic group of people with many eclectic views, some very intellectual, some very flamboyant, some prejudiced and one-sided, and all fascinating.

Olga was an extremely dignified lady who had this lilting voice with a sonorous Russian accent. In older age, she had these great sunken eyes that watched people like a hawk and then on occasion, if she was feeling gay, those big, dark eyes would sparkle.

Occasionally, Olga would talk to me about my mother (my mother died when I was quite young).

“Your mother never came into room,” Olga would make a grand flourish with her arm which would gradually rise as she spoke. She always seemed to be wearing an elegant black dress. She was a grand European lady, but she was also all business, but not in the sense that she liked commerce. Far from it, but at the root of her personality, Olga was both very serious and very grand.

And then after a pause demanding quiet, she would go on, “Your mother would make an entrance. Yes, when your mother came into the room, everyone would know she had arrived. They would turn and look.”

Olga was very impressed with the way my mother carried herself and Olga never would mention that my mother drank too much or say anything negative about my mother. In her mind, my mother was a lady. Instead, Olga focused on my mother’s entrance into a room. For Olga, making entrance was very important. It was in her mind a kind of lost art no longer known to people in America.

I saw Olga on and off over many years, at family events, in New York, in Southampton. She was always a grand and noble lady to me.

I understand that she could have her harder moments when she was quite stern with people. For many years she lived in New York with Vladdy Obolensky. Vladdy was Serge’s brother and a kind of polar opposite to Serge. He was a warm and friendly human being who liked his drinks. As an evening wore on his voice would get progressively louder and he would began to tell war stories about General Eisenhower and General Omar Bradley – Vladdy had met them both during the war and he would get wound up, excited about telling his story and almost be shouting. At those times Olga would quietly move in and grab his arm, look sternly, but quietly, and you would see her hand gradually press into Vladdy’s arm.

“Vladdy, I think it is time for us to go,” she would say. And Vladdy would suddenly become quiet and begin nodding.

“Yes,” he would say, now quiet and strangely calm, “We must be going.”

And they would go and walk back from 94th street to 98th. Sometimes, if it was late and dark, I or Ivan or one of Barbara’s daughters would walk back with them, just to make sure they arrived safely. Olga would walk with Vladdy, guiding him as she went, an old woman in black with a black overcoat with a dark fur collar, her back now a little hunched with time, Vladdy a little unsteady on his feet, but now accepting of the fact that he was headed home and the party was over.

I know Olga could also be stern with her two granddaughters, Lizi and Vari Obolensky. They were twins and the daughters of Ivan and Barbara.

When the period of the 60s and the 70s came about and many of the younger generation were experimenting with drugs, Olga had a little heart to heart talk with her granddaughters.

I am not sure exactly what advice and admonitions she gave to her granddaughters. I imagine it went something like this:

“So, children,” she might have said in her heavy Russian accent, no doubt wearing a black dress, “You are trying these drugs. I know about these things, children. Do not try to fool me. I was not born yesterday. What you are doing has been done before. It is nothing new. Leave it, it will do you no good.”

Whatever she actually said, I do not know, but I do know it surprised Vari and Lizi and made a deep impression on them.

I had the honor to attend Olga’s funeral. I remember it quite well. I was a little hung over and I remember standing in a line of relatives before her coffin. It was at the Russian Church a few blocks from Barbara and Ivan’s apartment. There was an Orthodox Russian priest, looking very stern and sinister with a great long gray beard, there were Russian princes and princesses of various ages and various demeanors, some old and worn and haggard, some young and vibrant, some of the younger generation who had grown up in America. There were other Russian people there, some men and women who had known Olga and family, perhaps in Russia and perhaps in America.

I remember I had a hard time standing still in that line by her coffin, but you could sense, a great lady had passed and stand you must. It seemed that ceremony went on forever, but eventually it ended and a bunch of Russians came back to Barbara and Ivan’s apartment, as people do after a funeral, to gather and speak some words of condolence and have some drinks, some food and remember the grand lady who had passed.

Russian funerals do not end with just a single ceremony. The process of morning takes two weeks. The next day Olga’s coffin was taken upstate to a remote area where a lot of Russian aristocrats are buried. There they had another funeral ceremony for Olga. I am not sure why there and I am not sure why they have the additional ceremony. Maybe they prefer to be buried where it is colder. Maybe, they think one ceremony is just not enough. I remember going up to this town and visiting another Russian church, one that was smaller and more authentic, one that seemed like something out of Dr. Zhivago. There was a blizzard outside and it gave me the feeling that I was no longer in America. I felt that I was now in Russia. I did not stay for the two weeks that Barbara and Ivan stayed there. I left that day, but I left with the feeling that Olga was now back in Russia.

Author’s note – As mentioned, Olga has written a book on her life which has been translated into English, but has not yet been printed.