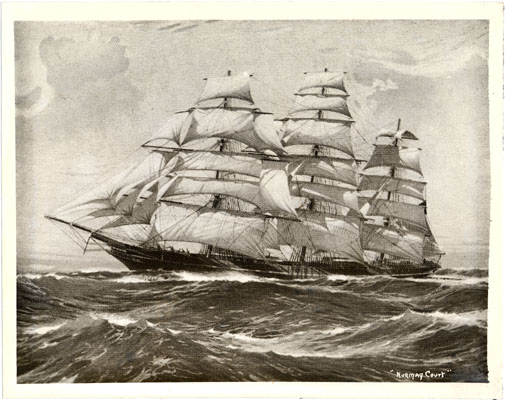

This is a photograph of a painting of the “Norman Court”, the clipper ship that my great, great, great uncle Andrew Shewan sailed around the world.

Sailing Clipper Ships Around the World

by Cecil C. Hoge

On my mother’s side, I am related to a long line of sea captains and pirates. It may seem extreme to call them pirates, but I am positive that this is true. My mother’s name was Barbara Ann Shewan and her side of the family was far richer and considerably less respectable than my father’s side. My father’s family come from a long line of respectable, well-bred preachers and ministers. Now I suppose every family can claim some famous relative or some prominent connections. How truthful the claims of my family is hard to know because much of our family’s heritage has been lost to the dimness of time and the forgetfulness of family members. That understood, my family was fond of claiming illustrious connections on all sides, as perhaps, some other families are.

My mother assured me that I am directly related to Bonnie Prince Charlie. She did mention however that my connection might not be completely on the up and up. This is because Bonnie Prince Charles was apparently very fond of women and in his travels came across a direct descendant of mine, a particularly buxom member of my Shewan family who was trying to make her mark as fledgling actress. I am not sure my descendant succeeded in the actress trade, but, according to my mother, she seems to have made her mark with Bonnie Prince Charles. The result supposedly being that I can legitimately claim that I am illegitimately related Bonnie Prince Charles. Royalty is royalty and however you get there is OK with me.

This is strange because on my father’s side, my grandmother has assured me that I am related to numerous Bourbon princes and the same good Bonnie Prince Charles on the Scottish side of the Hoge family. Recently, I checked this out on one of the many heredity sites that have been set up to assure everyone that they are related to famous people and sure enough I found a letter from William Hoge dating back to 1880 claiming that the Hoge family not only came from a long line of ministers (more than 50 by William Hoge’s account), but also were directly related to Bonnie Prince Charles.

This has got me thinking and wondering as to just how I am related to Bonnie Prince Charles on two sides of my family. Thinking about this too deeply can be disturbing and it seems that I may be related to the good Bonnie Prince Charles in more ways than I want to know.

Ancestry is like a drug. Once you delve into it, you cannot stop. In an effort to stop pondering my true relationship to Bonnie Prince Charlie, I started looking into the history of some of my other Shewan relatives. Here, there was some actual history I could follow. My grandfather Edwin Shewan owned a shipyard that did the repairs for the Atlantic fleet during World War I. He had a cousin Robert Shewan who ran a trading company located in Hong Kong and Shanghai called Shewan, Tomes & Co.

These are the old offices of Shewan, Tomes & Co., owned by Robert Gordon Shewan.

My wife gave me a book called “The Clipper Ships” because it listed some other prominent Shewans who were sea captains. In the 1850s through the 1870s there were two Shewans, father and son, both called Andrew, who sailed clipper ships from Aberdeen, Scotland or London, England to Hong Kong, Shanghai and other places in the Far East. As you may or not know, the British sailed up the Pearl River around 1842 and appropriated an island in the Pearl River that came to be called Hong Kong. I am not sure the Chinese were particularly happy about this, but the British warships that came to Hong Kong were extremely persuasive. It was called “gunboat diplomacy”.

The net result of this historical action was it gave my Shewan ancestors a place to dock and to trade. At the time of clipper ships, when they arrived from their 3 or 4 month journey across the oceans, traded goods for tea. What goods they traded for tea may be a bit like my possible family relationship with Bonnie Prince Charles…something that you may not wish to ponder too deeply. What can be said for sure is that many things were traded for tea, but over time, the most favored good of exchange came to be opium. I speak in general terms. This was because opium allowed traders to greatly leverage their buying power. Simply put, they got a lot more tea for opium. And while other goods were traded for exchange – American ginseng, animal furs, sugar, rum, pig iron, lead – nothing came close to the buying power of opium.

I do not know what my Shewan ancestors traded for tea, but surely they traded something – maybe it was nails, maybe it was wigs, maybe it was opium. However it happened, they must have found a medium of exchange acceptable to the Chinese sellers of tea. We must remember, whenever there is buyer, there is a seller. This tells me that whatever that medium of exchange was, it was acceptable to both parties. For in the case of my Shewan ancestors, they traveled back and forth from Scotland to Hong Kong and Shanghai nearly twice a year for over 20 years from the 1850s to the 1870s.

I know this because my wife also gave me another a book written by Andrew Shewan, my great, great, great uncle, called “The Great Days of Sail”. This book recounts Andrew Shewan’s reminiscences of sailing many of the great clipper ships of the day. The book, though quite technical, is very readable and quite easy to understand if you do not try figure out the many intricate and complicated parts of a clipper ship that he lists or the complex sailing terms he uses. There are interesting stories about sea shanties (songs sung by sailors), sudden gale winds, black squalls, encountering pirates, wild aboriginal natives, the tea trade, the leading clipper ships of the day, the monsoon season, running aground on reefs or shoals, being lost at sea or, as often happened, just plain disappearing.

This book is interesting to me for a number reasons. It is the personal account of one of my direct ancestors. It gives accounts of many of the trips of his father, Andrew Shewan, and himself, telling of the many hazards they faced, listing times it took to sail from Aberdeen or London to Hong Kong or Shanghai. Andrew lists the clipper ships involved and gives many other details, citing design differences, length, beam, tonnage at sea and number of crew. Most interesting to me were my ancestor’s stories of a ship called the Norman Court.

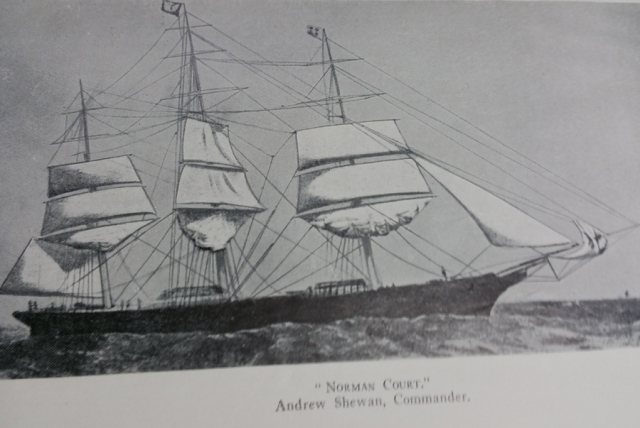

Here is another rendering of the “Norman Court” – it was supposed have been the second or third fastest clipper ship in world in her time.

The Norman Court, depicted above and at the beginning of this article, was one of the truly great clipper ships of the 1870s. Built in 1869 and first captained by Andrew’s father, Andrew Shewan, Sr., it soon came to be captained by Andrew himself. I have looked up the dimensions of this ship and it is quite imposing. She was 197 feet long, had a 33 foot beam and had net weight of 834 tons.

One of the reasons I am so fascinated by this story is the fact that I am importer by trade and I go to China and Korea once or twice a year. Hong Kong, Shanghai, the Pearl River delta, Canton (now known as Guangzhou) are all places that I regularly visit. Today, we import from China and Korea around 70 containers a year. I understand some of the many logistical problems of shipping goods from China today. I can only wonder and imagine what it must have been like to ship and transport goods in the days of clipper ships.

Knowing the length and beam of the ship that my great, great uncle sailed, I came up with some estimate of how many containers it might hold. I realize of course that there are many differences between loading a clipper ship with bulk cargo and loading containers on a modern container ships. A container can be placed on a container ship in 10 or 15 minutes, whereas a clipper ship had to load goods literally by hand. This was done by hundreds of “coolies” in China and hundreds of “stevedores” or “darkies” in Scotland or London. Please excuse my politically incorrect descriptions of the human beings involved – it is only to give you a feeling and perhaps a picture of the actual people who unloaded these goods.

Forgetting the differences of the two different methods of loading the two different kind of ships, I did a little calculation to get an idea of just how much stuff my great, great uncle shipped on a single trip in the Norman Court. I came up with the estimate that the Norman Court could hold the equivalent of 6 40′ containers. Now I realize that this estimate may be off because I do not know exactly the shape of the hold and I do not know the exact space taken by crew’s quarters and the captain’s deck house. In any case, 6 40′ containers is a lot of stuff. I know because we have a 24,000 square feet for our warehouse and if we take in more than 4 containers in a month we have real space problems. It takes us 4 to 6 hours to unload just one 40′ container. That is with 2 to 3 people, using a forklift.

It is also interesting to compare the times of unloading this amount of goods today and yesteryear. In the time of Andrew Shewan a clipper ship was unloaded in a day and half. If I compare this to our relatively mechanized process of loading unloading 6 40′ containers, we can do the same process in 3 to 4 days. There are, to be sure, some major differences. We are unloading goods directly from a 40′ by 8′ by 8′ steel box (called a container) parked at bay of our warehouse. In my grandfather’s time, he was unloading his 6 containers of goods directly out of the hull of a ship. This means, I presume, that goods had to be individually taken out by human beings. Presumably, these people had to carry the bales or boxes of these goods out through the hold of the ship, up to the deck. From there they most probably individually or collectively secured to a rope pulley and swung the goods over the deck and unto the dock. Each of these steps must have taken significant time, yet they they were able to unload the same amount of goods in less than half the time.

What could be the explanation of this strange fact? It really came down to two factors: 1) the huge number of people used to unload a ship in the 1860s and 1870s and the absolute critical importance of speed and time in the tea trade. When we unload a single container we use 2 to 3 men. When my great, great, great uncle unloaded the Norman Court, he used 200 to 300 men. The ship must have looked like an army of ants swarming over a very large fallen prey. Within 24 to 36 hours all the goods that could be unloaded from 6 containers were unloaded from the Norman Court. Of course, what made this possible was the number of people and the low cost of those people in relation to the high selling price of the goods being unloaded. The importance of speed and time in the tea trade was perhaps an even greater factor because the first teas to be unloaded always commanded the highest price.

The tea trade was essentially a race. A race to get to China in time to pick up the new season’s tea, a race to get back to London with the new season’s tea before other clipper ships. And since the quality of the tea was judged on the shortness of the travel (the shorter the trip the fresher and the better the tea), the price varied exponentially with the perceived value of the tea, with the first arrivals of tea always considered the best and always commanding the very highest prices.

For this reason clipper ships of the 1850s, 1860s, the 1870s were designed for speed and their ability to carry tea. The Norman Court was one of the very fastest clipper ships that the sailed in the tea trade. She held the second fastest time from Hong Kong to Aberdeen, Scotland, making the journey in just 93 days. Most journeys from China took 100 to 120 days, some took far longer. The risks taken during these trips were immense and total disaster was a frequent result. Many of these ships were lost at sea, foundered on rocks or reefs, captured by pirates, burned and scuttled, with the crew murdered in cold blood (for as my great, great, great uncle wrote, “Dead men tell no tales “).

You can say the tea trade of second half of the 1800s was somewhat similar to space travel in the second half of the 1900s. As in space travel of last 70 years, very few people actually took part in the trips and proportionally, those who did, experienced a high death rate. And as in space travel, the chances of death and disaster in sailing a clipper ship across the oceans was huge.

In the case of my ancestor and the Norman Court only 20 to 25 people sailed her on any given trip. I have seen a roster from my great, great uncle’s 1877 trip from New South Wales (i.e. Sydney, Australia). It lists 22 people, not including the captain, Andrew Shewan. Their ages range from 16 to 40, including a nephew, Alexander Shewan, who was 16 at the time. At the time of this trip, Andrew would have been 31. As you can see, sailing clipper ships was a younger man’s game.

So imagine 20 ro 25 people on one of the world’s fastest clipper ships, racing along at 15 to 18 knots (18 to 22 mph), in the China seas, in 1877, alone in ocean, except for an occasional sighting of another clipper ship with another 20 or 30 people. Admittedly, the risks were always there. Imagine sleeping only a few hours a day, which apparently the norm for a clipper ship captain, napping just one or two hours at a time, before being called on deck for the 19th appraisal of the ship’s situation of the day.

Imagine being at the helm of the Norman Court as you were racing along in a 40 or 50 mph gale. If it was a bright sunny day, and the seas were not too rough, it must have felt like you were one luckiest humans on the planet. Imagine you were the age of my great, great, great uncle, just 23, when he first captained the Norman Court from England to Hong Kong. You must have felt like the king of the sea.

Now imagine it is night and you are in a raging typhoon sailing through seas higher than you have ever seen, in waters that you not quite sure of. Is there land straight ahead? Are there reefs jutting out the sea in darkness? Are there unseen shoals that will run you aground and split your ship apart? In daylight will you find your ship swarming with pirates, who know the best policy and the best security is to steal all, murder all and burn all, except the valuables, because “dead mean tell no tales”?

Imagine finding yourself thrown from periods of ecstatic elation and high hopes to fear of imminent catastrophe and death, second to second, minute by minute, hour by hour, day by day, week by week, month by month. Imagine days and weeks of calm seas and fair weather. Imagine days and weeks of “dirty weather”, threat of pirates, wailing winds driving you onward, perhaps to rocks of doom.

Being a clipper ship captain must have been the most exciting and most terrifying job in the world.

Consider the following quotation from my ancestor Andrew.

“Though so staunch and tight, yet at times the whole fabric would tremble like a piece of whalebone. When we were driving her into a head sea. I have noted as I lay on the after lockers that after a heavy plunge as she recovered herself the after end would vibrate like a diving board when the pressure is released.”

I would imagine that this was not the best sensation in the world.

Well, I could probably write about my ancestor for many more pages, but I sense I am coming to the bearable limit. Let add a few points.

My great, great, great uncle wrote a 260 page book on “The Great Days of Sail”. He covered a great deal about the ships, the dangers faced, the excitement of the races, sea shanties, ship builders and other matters, but one thing is missing. That is what he was carrying in the Norman Court when he was going to China. Of course, he carried tea on the return from China and in some of the records it is said that he carried bales of cotton and lead from Manchester. But very little is said of what else he carried. There is some mention of rice, but it must be noted that Andrew Shewan went all over the Far East, visiting Japan, Korea, China, Singapore, Australia, India, Saigon, Bangkok and many other Far East locations.

So what was he carrying when he came to China? No doubt he did carry many legitimate cargoes, but it would be my guess that some times he was carrying opium. I do not say this lightly. I am talking about a direct ancestor. I do not wish to malign the gentleman. He was obviously one of the outstanding clipper ship captains of his time and that fact is mentioned by several other sailing books of the time. Nevertheless, in all the literature that I read I sense that there is more to be told and that there is something left unsaid.

We know as a matter of history that the principal commodity traded for tea during this period was opium. Actually, in reality, it worked a little differently. Clipper ship captains brought opium and traded opium for silver with other Chinese traders in Chinese ships. Then the clipper ship captains took the silver and traded it for tea, usually with the aid of an English trading company.

Now I also know that my great, great, great uncle was a prominent trader and shipper of tea. I know also that his brother, Robert Shewan, another relative, was the leading partner of a leading trading company called Shewan, Tomes & Co. I know also that the reason opium was used as a commodity of trade for tea was the simple fact that it bought more than other commodities. It would seem to be logical that my ancestor would use the effective commodity to trade for. Andrew was a principal owner of the ship, the Norman Court. He and Barings and Company were equal owners (both owned 16/64ths of the ship with some partners owning 8/64ths and others owning 4/64ths). I take this to mean my ancestor had an important say in exactly how things were done in the China trade for tea. At least, on the Norman Court.

Sailing Clipper Ships must have required great sailing skill, incredible stamina and great courage. It was a high stake game generally played by younger men. I will tell you the story of how Andrew Shewan came to be Captain of the Norman Court at the age of 23. He started on his first trips to China and the Far East when he just 16. He worked at that young age, first as a deck hand and then, after 3 or 4 years, the first mate on his father’s ship. The first trips father and son sailed on together were on the “Lammermuir” and “Chaa-Sze” clipper ships starting in 1960. In time, Andrew’s father became a partner and owner of the Norman Court with the Barings Company and other investors.

On the second trip out in the Norman Court, Andrew’s father began to feel very sick as they were coming through the English Channel. Father and son had conference on what to do. Andrew’s father was convinced that he was dying. Father and son put into the nearest port which was Darthmouth. Once ashore Andrew’s father began to feel somewhat better, but still felt unable to sail to China. Andrew told his father that he could take the Norman Court to China. Andrew’s father then went on to London and discussed this idea with the Barings Company. 2 days later Andrew’s father returned with the agreement of the Barings Company and Andrew found himself master and captain of the Norman Court at the age of 23. Father and son parted company. Sadly, Andrew’s father was right – he was dying and Andrew was never to see his father again.

So, if you can imagine thoughts of the young man, in command at 23 of one of the fastest clipper ships in the world, sailing literally to China with a crew of 20 plus other “souls”, knowing that now as captain he was responsible for the ship, the cargo and lives of all on board. Imagine then that Andrew also knew that his father was dying and that he would probably never see his father again. Andrew must have been conflicted with exultation, guilt, hope, sadness and adventure.

The first trip to China as master of the Norman Court proved to be very tough. Coming out into the Atlantic from the English Channel he almost sunk the ship when a halyard got stuck and the wind turned the Norman Court around. Andrew found himself in the extremely dangerous position of first being side swiped by a raging sea and then almost immediately turned completely around sailing backwards. Apparently, a clipper ship, under certain circumstances could sail almost as fast backwards as forwards. This may sound rediculous, but it also was perilous because the stern the ship could swamp in the following sea, upend and literally sink. Fortunately, Andrew acted quickly and was able to get the halyard unstuck and to swing the boat around so it began to sail in the normal way with the bow forward.

This probably was a very embarrassing beginning for the young master and it almost ended his career as captain before it began. Apparently, the trip was beset by many other challenges and dangers, from severe squalls, raging lightning, dead calms and almost running a ground. Andrew only quizzically remarks that it always seems to be the first trip (as captain) is the most challanging. No matter, he made it to China and he brought back tea in one of best times of that year. The Baring Company and the other investors were extremely pleased with his performance. This triumph must have been thrilling and yet dampened by the knowledge that his father had died.

There are two things I would like to know about that I have no information on. One is what Andrew Shewan thought of the countries he was passing through – he speaks of visiting Australia, Nairu Island, Indonesia, Vietnam, Hong Kong, Foochow, Shanghai and many other locations – and the other is what it really felt like to be at the helm of one of the fastest sailing ships on earth at a time when there were very few other ships crossing either the Atlantic and Pacific oceans.

In the absence of concrete information on these two matters, I can only speculate. And while it is pure speculation I think that my familiarity with trade and boating give me some idea of what Andrew Shewan’s thoughts might have been.

Regarding traveling to foreign countries starting at a very young age, I suspect it must have been a wonder and fascination to see other countries, meet other peoples and come to have some understanding of the greater outside world. I suspect he was both awed and in wonder of what he saw. And when he came home from his trips I suspect he tried to explain to others what he saw and he felt. And in the end, I think he found that those experiences and feelings were simply untranslatable. I think this because that is how I think of my foreign country trips whether they were to Europe or Asia.

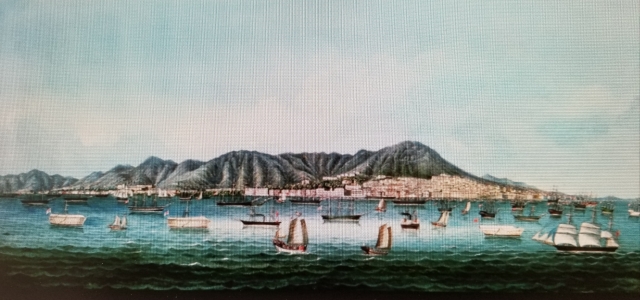

Here is an a picture of an old painting showing Hong Kong in the 1870s

How I would love to sit down with my ancient ancestor and share glass of some brown liquid and trade views, for example, of Hong Kong then and now. I have been to China more than twenty times and I have been to Hong Kong twelve or thirteen of those times. What would he make of the Hong Kong of today with its skyscrapers propelling themselves off of Victoria Peak? What would Andrew think of the Star Ferries, Hydrofoil Ferries, container ships, ocean liners, gambling ships, speedboats, great ocean yachts, ancient Chinese sailing junks, police boats and ancient Chinese motoring junks…all plying back and forth, up and down, in and out of the harbor of Hong Kong. What would he think of the giant bridges lurching across from island to island across the Pearl River, leading to highways taking you directly to mainland China? What would he think of Shanghia, Ningbo, Guangzhou?

This is an actual photo of Hong Kong in 1870

I wonder what he would think of the yellow brown haze that hangs over those cities today like the gray polluted fog it is. I wonder what he would think if he sat in a restaurant on 37th floor of a new high rise building on Kowloon Island, sitting in a restaurant, eating sashimi and pasta in air conditioned splendor overlooking Hong Kong Island in the evening, with a fine wine or brown beverage while a laser light show emanated from the far larger skyscrapers on Hong Kong Island on a warm sultry Hong Kong evening?

What was Hong Kong like when he saw it just twenty or so years after the British appropriated it from the Chinese? What did it look like? I imagine the sky was blue and clear, the surrounding mountains and lands mostly wooded and virgin. I imagine a few imposing white and gray European style buildings with pillars in front near the harbor on Hong Kong Island with large white European style mansions for the rich traders of the town set up on the hill overlooking the harbor. I imagine large, sprawling ugly warehouses near the harbor’s edge.

I imagine a sea of masts and ships and boats of every style…stately clipper ships, a few far larger British warships, China junks of every size, new and old merchants vessels from all over the world. By the harbor there must have been a chaotic symphony of sights, smells and sounds. Chinese food stands selling fresh fish, live chickens, snakes, insects among a sea of peoples, rickshaws, wagons and carts loading and unloading cargoes, swarming over ships, cargoes picked up in nets from the decks of ships and swung onto the shore in elegant, haphazard arcs.

How many people lived there in the 1860s or 1870s – twenty or thirty thousand, I would guess. Maybe only three or four thousand were British and European. The rest would have come for all over the world, seamen and laborers from all seven continents, hustling and bustling, eating, drinking, working, sweating, singing shanties, Chinese merchants hawking goods, European tradesmen buying and selling goods and services, a sea of laborers and/seamen swarming over the clipper ships, elegant British and European ladies strolling the town or being transported in rickshaws, wealthy traders and townsmen dressed in long jackets, vests and tall hats.

It must have been a scene. What I would give to ask my great, great, great uncle Andrew about what it really was like. What did he do when he arrived after a three or four month journey from England or Scotland? Did he go and have bath in some elegant hotel of the time and then prepare for night on town. Did he stay on his ship, living in his captain’s quarters while his ship was docked in Hong Kong. Imagine arriving in Hong Kong in 1873 at the age of 23, after safely navigating half way around the world, after 110 days at sea, after passing through countless dangers, after delivering safely all the crew and all the cargo. Imagine stepping off on to one of the many the docks of Hong Kong Island, with all the sights, the smells and the sounds I have tried to describe. My guess is that my uncle Andrew would be ready for a few days’ shore leave. Ready to party may not quite capture the pent up energy he must have felt.

This was one way to get around in old Hong Kong

Yeah, I would have liked to have been there and just follow him around, watching what he did, where he went. I am sure he would have had a certain amount of business to transact. He would have to meet people, maybe catch up with his brother, discuss about when the new teas would be ready for pick up. You must remember, since the time across the oceans varied trip to trip, according weather and sea conditions met, he would have given himself one or two month’s leeway for planning contingencies. This probably meant that each time he came to some Chinese or Asian port he might have to be there for many days or weeks.

Somewhere during his stays, I bet he found time to several enjoy fine and exotic meals, Western and Asian, and, perhaps, a few congratulatory drinks. I suspect, then as now, the compensating fact of long and hard travel was a nice meal and pleasant company. I can hope it was so for my great, great, great uncle Andrew. And I would love the opportunity to trade stories, although asymmetry of the exchange might prove embarrassing. He, perhaps, would not be impressed with my travel travails of losing luggage or missing planes. I feel sure however that some of our experiences could be considered parallel – the experience of visiting a new city halfway around the world, the experience of dealing with different cultures and cuisines, the experience of having things change once you got there – I would guess there are indeed some similarities in what my uncle and myself do when traveling. I also sure that I might find profound differences philosophically, spiritually and physically between myself and my great, great, great uncle Andrew. Since a meeting does not seem imminent, I will worry about sorting that out when the occasion arises.

More than anything I would like to know from Andrew what it was like to be at helm of a fast clipper chipper ship knowing that you are one of a few hundred men who shared that experience. He would, no doubt, have had a lot to say about it. Maybe, he would not be eager to share his experiences, thinking it a private matter, not possible to be shared with others. Maybe, he would try to explain it all – giving me details of what it was like to sail through a typhoon, meet dangerous natives, be becalmed on flat ocean for days, drifting aimlessly, face down pirates who want to murder you for the cargo you are carrying, sail through thunder and lightning with massive waves drenching the whole length of the ship every two minutes.

I can say for sure he did things and saw things that very few did or saw. Those experiences must have been the most important of his life. He wrote a 260 page book about it and yet, after reading it, I feel as if I know only a very small portions of what his real experiences were. I wish I could know more about that man. He must have been some guy. I know he would have much he could tell me, but separation of time and space makes that impossible.

I have never been able to totally plumb the mysteries of my relationship to the Shewans. I was born and raised in England but my mother was sent to Peterhead, in Scotland every year for the school year. She was born in 1915. She stayed with her great aunts (her grandmothers sisters) and the living room had paintings of Clipper Ships. Andrew Shewan was the aunts brother or cousin and every year they sent shortbread to a cousin in Shanghai for Christmas. She told me he was Master of the Norman Court and raced the Cutth Sark in the tea grade.I have a photo of an oil painting of the Norman Court that I purchased in Greenwich and I also have a copy of Andrew Shewan’s book. I live in Sausalito, close to San Francisco.